BY HENRIK DAHL

Book covers in psychedelic literature are rarely discussed. Yet they are part of a design tradition that goes back at least to the mid 20th Century.[1] Admittedly, some covers reflect the content poorly. But a considerable amount of them are made with great care and effort, often displaying intriguing, original and thought-provoking designs. Although usually ignored and overlooked by researchers, the field of book design may provide us with a better understanding of the genre and psychedelic culture as a whole.

A Design Tradition

There are several good reasons for analysing book design in psychedelic literature. For instance, book covers may reveal a lot of information about the times they were made. Obviously, they show the technical progress that has taken place over the decades. Book covers can also reveal a lot about our relationship with the other. One may ask what it means to place a shaman from the rainforest on the front cover. Is the motif a necessary reflection of the content of the book, or is the publisher simply expressing anachronistic fantasies of life in the wilderness?

Before looking into cover design in the genre a few words should be said about what defines it. The common definition seems to be that these are works about psychedelics and/or the psychedelic experience. They can be non-fiction or fiction, even though the former is the most common. Writers may for example include scientists, journalists, researchers or fiction authors. Some of the titles are in the grey zone. These include books where only a minor portion of their content is about psychedelics. Books about cannabis are generally not included in the genre. Defining psychedelic literature in the way just described is far from perfect. Clearly there are books that do not meet with the criteria, yet are still considered belonging to the genre. One such example is the 1971 book Be Here Now by Ram Dass. Despite not being about mind-expanding drugs per se, the book has a literary style and visual aesthetic that makes it part of psychedelic literature.

It may look like psychedelic literature is only a minor niche in the world of book publishing, but a few authors in the genre have actually become hugely successful. One such author is Carlos Castaneda. During his lifetime his books were sold in at least 10 million copies, and none of his titles have ever gone out of print.[2] Castaneda’s controversial début The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (1968) is probably one of the most well-known works in psychedelic literature. The book has gone through several different cover designs, and it is presumable that they have played an important part in its success.

When writing this essay only front covers were taken into consideration. The spine and the back cover are also very important elements. Still, it is the front that we mostly think of when we refer to a certain book design. It is also the front that is used whenever a book is marketed by a publisher, or reviewed by the media. In addition, all the books referred to in this piece are in English and have at some point been printed on paper.

*

Although psychedelic looking imagery had been used on book covers before the 1950s, it was the design of Aldous Huxley’s 1954 essay The Doors of Perception that marked the start of the publication of books on psychedelics where the content is reflected on the cover. The dust jacket of the original cover design of Huxley’s seminal trip report contains one of the most used and, admittedly, most powerful symbols seen on psychedelic literature, namely the eye. Since The Doors of Perception numerous books in the genre have been published showing one or several eyes on the front cover. A book about, say, LSD therapy will probably look very different from a book about ayahuasca shamanism. There is, however, a psychedelic aesthetic that runs through the decades. Some motifs, such as the eye, occur over and over regardless of which psychedelic is discussed.

In a sense a book cover can be regarded as a map. It can reveal ethnocentric attitudes, not to mention those relating to race, globalisation, gender, animals, the environment and tourism. Moreover, when looking into the topic of book design in psychedelic literature one soon finds that book covers reflect which psychedelics were the ones most in vogue in a certain era. Generally speaking, it seems every decade from the 1950s and onwards in psychedelic literature is associated with a specific psychedelic. The seminal works of Aldous Huxley and Henri Michaux in the mid-1950s were based on their experiences with mescaline, while in the 1960s Alan Watts, Timothy Leary and numerous other authors turned to the topic of LSD. The mid-seventies saw a shift to psilocybin mushrooms. Major works from that era include those by Terence and Dennis McKenna. Terence McKenna reappeared in the early nineties with several books, again focusing on psilocybin mushrooms, but also DMT and ayahuasca. During the 21st Century there has been a growing interest in psychedelics used by indigenous peoples. This has resulted in a number of books on ayahuasca (e.g. by psychologist and Leary associate Ralph Metzner and Australian journalist Rak Razam), but also accounts of previously lesser-known drugs such as iboga (the perhaps most well known being that of journalist and Reality Sandwich co-founder Daniel Pinchbeck).

It seems very few designers get to specialise in psychedelic literature, that is, unless one gets to work for one of the very few publishers focusing exclusively on the genre. When going through the credits of a number of books published in recent years by Park Street Press, a subdivision of American publishing company Inner Traditions, I noticed that the name Peri Swan appeared repeatedly. Swan’s covers often show heavily edited photographs or graphic shapes – motifs include indigenous peoples, plants and animals – while typefaces usually are written in golden serif typography (i.e. letters with “feet”). In addition, Swan’s work is characterised by strong colours and the designs clearly have a psychedelic aesthetic.

In a sense a book cover can be regarded as a map.

Many covers in psychedelic literature are based on artworks created by professional visual artists. For example, in the early 2010s paintings by Fred Tomaselli were featured on no less than three book covers: Nomad Codes: Adventures in Modern Esoterica (2010) by Erik Davis, Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s (2010) by David S. Rubin and Are You Experienced?: How Psychedelic Consciousness Transformed Modern Art (2011) by Ken Johnson. The latter two are books on psychedelic art. Interestingly, Tomaselli has distanced himself from the genre: “My art is informed to a certain degree by psychedelic art but it’s in concert with many different ideas and ‘isms,’ so I don’t really consider myself a psychedelic artist per say.”[3] Other artists whose art have appeared on book covers are Alex Grey and Anderson Debernardi. Grey’s art is featured on the 2001 book DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor’s Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences by Rick Strassman. The painting – arguably one of Grey’s finest – is called Dying and shows a man lying in a reclining position, presumably in an altered state, while being surrounded by a swarm of eyes emanating from a centre that radiates white light. As for Debernardi, his painting Shaman Cosmico is featured on Inner Paths to Outer Space: Journeys to Alien Worlds through Psychedelics and Other Spiritual Technologies (2008) by Rick Strassman et al. The Peruvian painter draws inspiration from ayahuasca visions, resulting in finely detailed and colourful artworks, which often include non-human animals, plants and beings belonging to the spirit world.

What is the real purpose of designing books? Andrew Haslam, designer and course leader at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London, says in Book Design: A comprehensive Guide that, “A book cover is a promise made by a publisher on behalf of an author to a reader”.[4] Book design in psychedelic literature is, of course, no different. In the second part of this essay I will discuss the imagery that is the result of these promises.

An Attempt at Defining the Endless Stream of Psychedelic Imagery

“The Eyes are wings of the Soul – they see us to Heaven.”[5] – Alex Grey

As a starting point for discussing psychedelic book covers, I have put the most common motifs into three categories. They are:

– Mushrooms and plants

– Human and non-human animals

– Abstract shapes and typography

Obviously, if pushed, many book covers can be placed in more than one category. The purpose of creating these categories is to show major currents in the designs. Further research may show that the categories need to be improved upon or altogether redefined. However, at the present moment I find them a useful tool when discussing the covers.

In the Mushrooms and plants category one finds various psychoactive drugs. Mushroom species include Psilocybe cubensis, Psilocybe semilanceata and, of course, Amanita muscaria, also known as the fly agaric. Examples of plants are peyote, Banisteriopsis caapi and Datura.

The Human and non-human animals category includes the following subcategories: Indigenous peoples (often South or Central American; typically shamans); Portraits of authors (usually found on biographies); The human body (body parts such as the eye); Non-human animals (e.g. birds, snakes and dolphins).

The Abstract shapes and typography category includes various shapes such as spirals, circles and concentric objects. These are often symbolising visions seen while in altered states of consciousness and needless to say usually have a psychedelic aesthetic. This category also includes typographic covers, which consist of typography only and are devoid of images.

Before looking into the most common themes, a few words should be said about imagery that is only rarely seen on the covers. For example industrially manufactured objects are almost never included. A rare example is the previously mentioned Be Here Now (1971) by Ram Dass, which includes a chair placed in an abstract shape where lines and the phrase “Be here now” constitutes a yantra. In addition, objects such as vehicles are seldom included on the covers, even though the 2008 edition of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe, in accordance with the story, has a bus on the front cover. Another example of an unusual motif is seen on Millbrook: The True Story of the Early Years of the Psychedelic Revolution (1977) by Art Kleps, which features a picture of the estate.

I. Mushrooms and plants

For obvious reasons there are mushrooms aplenty on front covers of psychedelic literature. The perhaps most commonly depicted species is the Amanita muscaria. An early example of psychedelic literature with this mushroom species on the front cover is R. Gordon Wasson’s 1968 book Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Other, more recent, examples of front covers featuring fly agarics are the 2008 paperback edition of Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom by Andy Letcher, and Arik Roper’s 2009 art book Mushroom Magick: A Visionary Field Guide, featuring Roper’s art on the cover. Since the Amanita muscaria is so iconic and eye-catching it is very likely we will continue to see front covers depicting this mythological mushroom.

Unlike the brownish psilocybin containing species, the fly agaric screams for attention.

Even though Amanita muscaria is found growing on many locations around the world, it is only rarely used as a mind-expanding drug. Those who have experimented with the mushroom seem to find it somewhat disappointing, and, at higher doses, unpredictable and disturbing with unwelcome side effects. But this fascinating white spotted red mushroom has nevertheless become a staple in psychedelic imagery. The fact that psilocybin containing species such as Psilocybe cubensis are far more commonly used as a mind-expanding drug doesn’t seem to make any difference; their visual appearance simply can’t compete with the Amanita muscaria.

Unlike the brownish psilocybin containing species, the fly agaric screams for attention. Obviously, this is a quality that appeals to most designers and publishers. The smaller Psilocybe semilanceata, or the liberty cap as it is also called, has a form – usually conical to bell-shaped with an umbo – that is actually more easily depicted than the fly agaric. Still, the Psilocybe semilanceata is rarely seen on book covers. The mushroom is featured on the front cover of A Guide to British Psilocybin Mushrooms by Richard Cooper. Published in 1977 and, after being pirated, followed by a new edition in 1994, this thin little book contains a series of beautiful illustrations credited to Graeme Jackson, which are also used on the front covers. Jackson has a poetic and slightly romantic yet seemingly precise style making the title worth looking up for the drawings alone.

An example of a cover that includes both mushrooms and plants is the 1993 edition of True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author’s Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil’s Paradise by Terence McKenna. Originally published as an audio book in 1984, it became highly influential and is of course a classic in psychedelic literature. The cover design of the print edition from 1993 is credited to Nita Ybarra, while the illustration on the front is by Peter Siu. In the middle of the front cover is a rectangular plate with Siu’s illustration as well as title and author name, the latter written in a bow shape over the illustration. Around the plate are stylised leaves. The overall aesthetic harks back to Art Nouveau and is, of course, decidedly retro. At the centre of the cover is an illustration of a large mushroom with a smaller one at each side of it, and, at the left, there is a bird sitting on a branch. More than 20 years after it was published, it is still a cover that perfectly reflects its content.

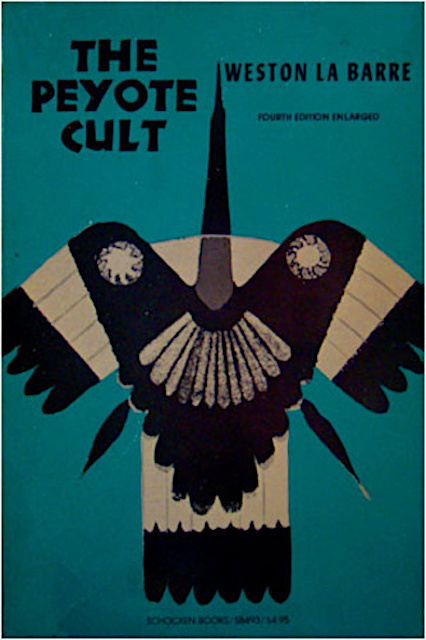

Peyote is a well known psychedelic, but books exclusively on the cactus are rarely published today. The fairly low interest in the plant possibly has to do with it being overshadowed by the current popularity of ayahuasca shamanism. Peyote is also growing very slowly, making it substantially less accessible than many other psychedelics. Even so, from a historical perspective peyote plays a very important role in psychedelic culture. It is assumed that peyote has been used ritually among indigenous peoples in North and Central America for millennia. As for the western world, trip reports started to appear in the late 19th Century describing peyote intoxication, and, as mentioned before, in the 1950s, both Aldous Huxley and Henri Michaux experimented with mescaline, the active ingredient in peyote. In addition, the beat writers of that era were known to use the plant. An example of a cover design featuring peyote is the 1976 book Peyote Hunt: The Sacred Journey of the Huichol Indians by Barbara G. Myerhoff. Based on a photo by Myerhoff, the front cover of the eleventh paperback printing shows a basket of newly harvested peyote buttons.

II. Human and non-human animals

Indigenous peoples

When indigenous peoples are depicted they are often shamans originating from South or Central America, where there is a strong tradition of using plant based psychedelics. For example, the front cover of the 1992 edition of Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing and Hallucinogenic Powers by Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann, features a photograph of a medicine man called Salvador Chindoy of the Kamsá tribe in southern Colombia. The photo is taken by Schultes, while the cover design is credited to Pat Gorman Design. Framing the photo is an orange graphic pattern, while outside of it are illustrations of psychedelics. Just like its contents, the cover is one of the classics in psychedelic literature.

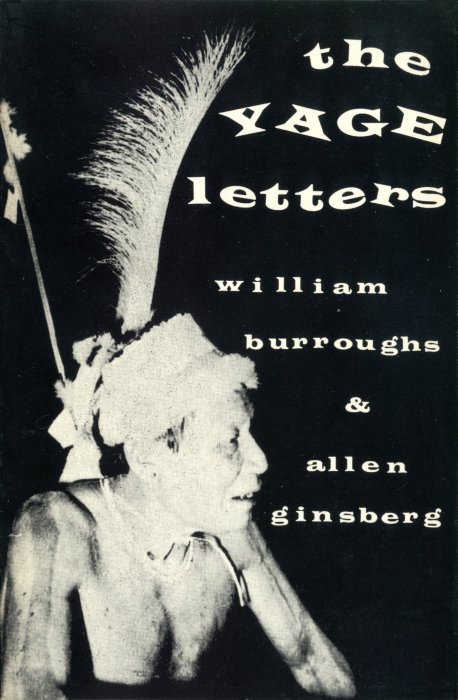

Other examples of front covers showing indigenous peoples are the 1963 and 2001 editions of The Yage Letters by William S. Burroughs, featuring a black and white photo of a shaman, and Peyote Vs. The State: Religious Freedom on Trial (2009) by Garrett Epps, which has an illustration of two Native American shamans engaged in ritual activity.

Clearly, western culture has had a huge impact on indigenous peoples around the world, yet on the covers they still often appear somewhat unaffected by the west, as if they were frozen in a previous time. Although not wanting to downplay the designs mentioned above, there is reason to be sceptical of some of the covers that are featuring indigenous peoples. Of course, this can also be said of their contents. In his aforementioned book Shroom, Andy Letcher questions the way Mazatec shaman Maria Sabina has been portrayed by researchers. Included in the book is a picture, taken in the 1980s, of her playing an acoustic guitar. As Letcher points out, westerners, presumably wanting her to be thought of as a primitive curandera, failed to mention she played the instrument.[6]

Portraits of authors

As in most literary genres, portraits are usually seen on biographies. The perhaps most well known autobiography in psychedelic literature is LSD: My Problem Child by Albert Hofmann. The cover of the 2013 edition of the book shows the scientist in glasses wearing a white laboratory coat, while the 2005 edition features a photo of him without glasses, dressed in a sweater and grey-haired. Interestingly, both covers feature the word “LSD” in a very big font size, indicating that, generally speaking, people are still more familiar with the name of the drug than the name of its discoverer. As a side note, books written by famous authors, such as Huxley or Castaneda, often have their names in big letters on the front covers.

When looking at psychedelic literature from a gender perspective, one soon finds that the genre is heavily male-dominated. This is of course reflected on the cover designs, where very few women are depicted. Examples of covers showing portraits of authors who are women include Marlene Dobkin de Rios’s 2009 book The Psychedelic Journey of Marlene Dobkin de Rios: 45 Years with Shamans, Ayahuasqueros, and Ethnobotanists, and the 2000 edition of Sisters of the Extreme: Women Writing on the Drug Experience by Cynthia Palmer and Michael Horowitz. Featured on the latter are, among others, Grace Slick, singer of 1960s psychedelic rock band The Jefferson Airplane. Incidentally, the first edition of the book, published under the name Shaman Woman, Mainline Lady: Women’s Writings on the Drug Experience (1982), features an illustration of an unidentified pipe-smoking woman surrounded by Art Nouveau styled vegetation. The cover brings to mind 1960s poster design, which was often heavily influenced by Art Nouveau.

The human body

As mentioned earlier, the eye is a very common image on front covers in psychedelic literature. Some examples where a single eye is central to the design include front covers of Doing Your Own Being (1973) by Ram Dass, Cleansing the Doors of Perception: The Religious Significance of Entheogenic Plants and Chemicals (2000) by Huston Smith and The Psychedelic Future of the Mind: How Entheogens are Enhancing Cognition, Boosting Intelligence, and Raising Values (2013) by Thomas B. Roberts. The eye is clearly a well-worn cliché in psychedelic book design, and no designer will get any points for originality for putting another eye on the cover. Still, given that it is a powerful symbol of perception it is no wonder the eye is used repeatedly.

When it comes to other individual parts of the human body, faces are sometimes included, as exemplified by the cover of The Psychedelic Renaissance: Reassessing the Role of Psychedelic Drugs in the 21st Century Psychiatry and Society (2013) by Ben Sessa, where a part of a face of a man is seen. Other body parts are very seldom used in psychedelic book design, a rare exception being the front cover of the 1986 edition of Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide by O.T. Oss and O.N. Oeric – pseudonyms for Terence and Dennis McKenna – where the imagery of Cathleen Harrison’s illustration includes a hand.

Non-human animals

Non-human animals are fairly common on the covers of psychedelic literature. For example, a dolphin is included on The Scientist: A Metaphysical Biography (1996) by John C. Lilly, who, in addition to inventing the isolation tank, made research on dolphin communication. Another cover showing a dolphin is Psychedelia: An Ancient Culture, A Modern Way of Life (2012) by Patrick Lundborg. It is based on a painting by Anderson Debernardi and includes several other animals such as snakes and a bird. Birds are also seen on several Castaneda covers, such as the paperback of the 30th anniversary edition of The Teachings of Don Juan (1998).

The butterfly – a symbol of transformation – is occasionally seen in psychedelic imagery. Still, it is not as common on book covers in psychedelic literature as one may think. A butterfly is included on the cover of the 1993 edition of The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens and the I Ching by Terence and Dennis McKenna. The inclusion of the motif makes sense; Terence McKenna worked as a butterfly collector before he became a writer. There is also a butterfly on the front cover of the 2003 book Magic Mushrooms by Peter Stafford.

It appears the archaic “back to the nature” sentiment of the psychedelic experience goes well with non-human animal imagery. Yet psychedelic culture’s relation to non-human animals clearly have a troubled past given that thousands of them have been used – and killed – in scientific animal testing involving psychedelics.

III. Abstract shapes and typography

Abstract shapes

These are very often used on psychedelic book design. Typically they have a psychedelic aesthetic in the sense that they are obviously meant to make the reader associate to visions one may experience while in altered states of consciousness. They can take many forms. Spirals are often seen, an example being the cover of 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl (2007) by Daniel Pinchbeck. Designed by Gretchen Achilles, it consists of a white spiralling shape on a green background. Compared to other books in the genre, the cover design is quite minimalistic. Still, the illustration has an alluring, somewhat psychedelic, quality.

Concentric shapes – especially circles – are also a common motif. Visual artist Fred Tomaselli often includes them in his paintings, making his work especially interesting for publishers of psychedelic literature. The three previously mentioned books that have his art on the cover all feature concentric circles. This is perhaps most prominent on Are You Experienced? by Ken Johnson, which features a detail of Tomaselli’s 2009 artwork Big Eye.

Typographic covers

In 1900 basically all covers were typographic.[7] Later, book design changed radically thanks to the technological developments that took place in the 20th Century. Today’s typographic covers have a wide diversity; some express an experimental playfulness, while others signal an academic seriousness. An example of the latter is the design of LSD, Man & Society edited by Richard C. DeBold and Russell C. Leaf. On the front cover of the 1968 paperback edition the title is written in large letters in serif typography, while the editor’s name is in a smaller font size at the bottom. Included on the front cover is also a short description saying that the facts about LSD are “soberly stated” in the book. In the introduction the drug is described as “a serious problem”,[8] and contributing author Donald B. Louria suggests “severe penalties” for those who manufacture or sell LSD.[9] The book title is written in red letters on a black background. Red is, of course, often used as a symbol of danger.

What may come as a surprise to some is that the very first cover of Carlos Castaneda’s The Teachings of Don Juan – originally written as a master’s thesis at UCLA – looked completely different compared to how the book was packaged in the seventies and onwards. Instead of imagery such as birds and shamans, the 1968 edition had a very clean typographic cover. Clearly, this formal looking design gave the book an air of academia. As readers of psychedelic literature are well aware of, the anthropologist was accused of making up most of his experiences with Don Juan. Regardless of what was the actual truth behind Castaneda’s writings, the covers that followed on later editions and printings make the book appear more like fiction literature than a scientific work.

*

In the mid-1990s, while on a holiday in London, I bought my first book in psychedelic literature. It was a thin, stapled book – a booklet is perhaps a better word for it – with an intriguing cover. The book in question was the previously mentioned 1994 edition of A Guide to British Psilocybin Mushrooms by Richard Cooper. Some 20 years on I still read psychedelic literature, and after finishing this essay I can’t help to think that the cover design of that first book had a strong impact on my interest in the genre.

During my research I went through a great number of book covers. A few of them are sitting on my bookshelf, while many of them were found online. I also had the great fortune to access the drug bibliography and cover scans of designer and former book collector Jdyf333. His bibliography contains over 1400 titles, complete with publishing data and personal comments, while his collection of scans features over 4000 book (and magazine) covers. Going through all the covers, I realised that in the past I had not given the designs any deeper thought. I assume I was too focused on their contents to analyse their designs. This is not to say I did not appreciate a beautiful cover when I came across one; they have always been an important part of the reading experience. I just did not realise how important, possibly because they are, strangely enough, almost never discussed. Hopefully this will change with the growing interest in the visual aspects of psychedelic culture, which has been seen in recent years.

By Henrik Dahl

Posted on February 2, 2017

This article was originally published in the The Fenris Wolf 7 (Edda Publishing, 2014).

Henrik Dahl is a journalist and critic specialising in psychedelic culture and art.

Featured image: Front cover design (detail) of The Pleasure Seekers: The Drug Crisis, Youth and Society (1969) written by Joel Fort.

Notes

1. One could argue that psychedelic literature existed long before the 1950s. For instance, in 1896, peyote trip reports by Dr. Eshner and Dr. S. Weir Mitchell were published in The British Medical Journal. However, psychedelic literature as we know it today was unseen of before the mid-20th Century.

2. Marshall, Robert. “The Dark Legacy of Carlos Castaneda.” Salon.com, 2007. Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/2007/04/12/castaneda/

3. Taaffe, Philip. “Philip Taaffe and Fred Tomaselli in Conversation, with Raymond Foye and Rani Singh.” Philiptaaffe.info, 2002. Retrieved from http://www.philiptaaffe.info/Interviews_Statements/Tomaselli-Smith-Taaffe.php

4. Haslam, Andrew. Book Design: A Comprehensive Guide. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2006, p. 160.

5. Twitter.com, 15 January 2014. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/alexgreycosm

6. Letcher, Andy. Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom. New York: Harper Perennial, 2008, p. 108.

7. Haslam, op.cit., p. 160.

8. DeBold, Richard C. and Leaf, Russel C. (Eds.). LSD, Man & Society. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. 1968, xii.

9. Ibid., p. 44.